|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

| Ballets

Russes (1909-1962)

The Ballets Russes made dance history. As one of the earliest gay-identified

multinational enterprises, it was also important in gay history.

Although "ballet russes" might sound like a generic term,

meaning simply Russian ballets, it actually refers to the hallmark of

twentieth-century theatrical dance. However, the Ballet Russes not

only represents a crucial turning point in dance history, but it is a

milestone in gay history as well. The brainchild of impressario Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929), a gay

Russian nobleman who fell in love with the nineteen-year-old Vaslav

Nijinksy, a rising star in the Imperial Russian Ballet, the Ballets

Russes might be seen as one of the earliest gay-identified

multinational enterprises. Although the first Ballets Russes company was not officially

organized until 1911, it dates from 1909, when Diaghilev assembled a group

of dancers from the Imperial theaters and charged a brilliant young

choreographer, Michel Fokine, to create a repertoire to spotlight

Nijinsky's great talent. Under the patronage of Tsar Nicholas II, Diaghilev brought his Ballets

Russes to Paris in May 1909. Its success was immediate and

sensational. The brilliant artistry of the dancers, including Tamara

Karsavina as well as Nijinsky, combined with erotic choreography,

startlingly modern music, and strikingly original scene designs, altered

the course of dance history, making the Ballets Russes the vanguard

of distinctly twentieth-century art. For the next twenty years, Diaghilev never failed to discover fresh

genius, featuring the work of then uncelebrated composers and artists such

as Igor Stravinsky, Jean Cocteau, and Pablo Picasso. His company

specialized in ballets of "total theater" in which all aspects

of the productions were important, although the Ballets Russes was

especially noted for its superb male dancers. After he fired Nijinsky in 1913 (when the dancer married a Hungarian

admirer, Romola Pulszky), Diaghilev took as his lover the

eighteen-year-old Léonide Massine, who was to serve as the

company's principal dancer and choreographer for the next seven years. In

1924 Diaghilev met the last of his protégés and lovers,

seventeen-year-old Serge Lifar, who became the company's premier

danseur and later became director of the Paris Opera Ballet. After the Russian Revolution, the Ballets Russes, which had

never performed in Russia, was permanently cut off from its homeland.

Diaghilev featured many Russian émigré dancers, but turned

increasingly to French composers and painters as collaborators for his

choreographers. In the Ballets Russes gay men, whatever their nationality, were

highly visible and their influence extended outward from ballet into

related art forms such as cinema, painting, music, and fashion. At Diaghilev's untimely death in 1929, the original Ballets Russes,

then based in Monte Carlo, dissolved. But in 1931 many of his dancers and

choreographers were reunited in a company formed by Colonel V. de Basil, a

former officer in the Russian army. The new company incorporated

Diaghilev's repertoire, but also developed new stars--notably the

celebrated "baby ballerinas," Irina Baronova, Tamara Toumanova,

and Tatiana Riabouchinska--and new ballets. Among the new works commissioned by de Basil's Ballets Russes

was David Lichine's Cain and Abel (1946), perhaps the first overtly

homoerotic

ballet in history. The work features the two title dancers nearly nude in

a sensual pas de deux. Colonel de Basil's Ballets Russes toured extensively in South

America and Australia and survived the terrible vicissitudes of World War

II, but disbanded in 1952 after the Colonel's death. In 1937, an artistic schism occurred within de Basil's company and

dissenters, led by Léonide Massine, formed a rival company in

Monaco. Financed with American money and directed by Serge Denham, a

Russian banker, the new company was called the Ballet Russe de Monte

Carlo. Massine strove to continue the great tradition of the original Ballets

Russes. With the outbreak of World War II, the new company relocated to the

United States where, by virtue of its transcontinental annual tours, it

became the national ballet company of America. For more than twenty years,

until its demise in 1962, it visited as many as 100 towns and cities in a

season, astonishing audiences with its glamour and awakening in many

isolated gay men the dazzling reality of a gay-friendly artistic milieu. Some of these men first exposed to dance in this way searched out

ballet studios and eventually had dance careers of their own. Among the most important legacies of the Ballets Russes is its

function as a nursery to other companies. Many dancers and others

associated with the various Ballets Russes companies opened schools

throughout the world. They produced dancers trained in the great

tradition, as well as an audience prepared to support civic ballet

companies. Nearly all of the most prestigious international ballet companies

descend directly or indirectly from the Ballets Russes. And without

the Ballets Russes, we would not have their saucy offspring, Les

Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, the all-male American troupe

triumphantly touring the world, en pointe and en travesti. |

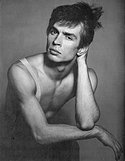

| Taylor,

Paul (b. 1930)

Dancer and choreographer Paul Taylor has been an important presence in

American dance since the 1950s. |

Paul Taylor in 1960. |

|

One of the most influential dancers and choreographers of the twentieth century, Paul Taylor has been an important presence in American dance since the 1950s. When he wrote his autobiography, at the age of 57, Taylor revealed his ambivalence about sex and gender in dance and life, remarking that to "pick partners of consistent gender would've run against an arbitrary streak" that he considers one of his strengths. He was born Paul Belleville Taylor, Jr. on July 29, 1930 in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. After his parents divorced he was shuttled between various friends and relatives as his mother worked full-time in a restaurant. Taylor attended Syracuse University on an athletic scholarship as a swimmer and majored in sculpture and painting. He left school during his junior year to study with Martha Graham, Anthony Tudor, and José Limón, among others. He then danced with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (1953-1954), Pearl Lang (1955), and then the Martha Graham Dance Company (1955-1962). Taylor established his own company in 1964. After appearing at the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, the company began to tour all over the world. Several of his company's tours have been sponsored by the United States State Department. At 6'3" Taylor is a large man for a dancer, but he danced with a startlingly fluid movement. His lyrical approach gave barefoot modern dance a neo-classic style with a virtuosic edge. When Taylor retired from dancing in 1974 at the age of 44, many felt that this very good choreographer was on his way to becoming a great one. Many of his dances have been performed by major ballet and modern companies around the world, especially Aureole (1962), Esplanade (1975), Airs (1978), and Arden Court (1981). No other modern dance choreographer is so popular with ballet companies and their audiences: over fifty ballet troupes have performed his pieces. Taylor's fertile imagination has created over 100 dances. Perhaps most impressive is the expressive range of his work, which extends from the despairing Last Look (1985) to the critical social commentary of Cloven Kingdom (1976) and Big Bertha (1971) to the exuberant comedy of Ab Ovo Usque Ad Mala (1986). While Taylor has collaborated with such established visual artists as Robert Rauschenberg, Gene Moore, John Rawlings, and Alex Katz, another designer of his dances, "George Tacet," is Taylor himself. Since the 1960s, Jennifer Tipton has lit almost all of Taylor's dances. From its beginning the Paul Taylor Dance Company was distinguished by the look of its male dancers. Typically, they are larger than men in other companies. Their size gives Taylor's choreography a muscular weight. With rare exceptions, Taylor has treated his company as a true ensemble, equally distributing solo roles among them. Several former members of the Paul Taylor Dance Company have gone on to establish their own companies, which is another indication of Taylor's influence on the shape of twentieth-century modern dance. Among these former members are Laura Dean, Pina Bausch, Daniel Ezralow, David Parsons, Twyla Tharp, and Dan Wagoner. Dancer and budding choreographer Christopher Gillis (1951-1993) had been designated Taylor's heir apparent. However, he died of AIDS complications and the company's future leadership is now uncertain. In 1987 the company's concerts began to include work by choreographers other than Taylor; and in 1992 Taylor established a junior company, Taylor 2. In his chatty autobiography Private Domain (1987), Taylor mentions sexual encounters with both men and women, yet concludes that "As far as romance goes, I can forget it." He seems to find his responsibility for his "family" of dancers a satisfying substitute. Same-sex partnering appears in works such as Esplanade (1975), Kith and Kin (1987), Company B (1991), and Piazzolla Caldera (1997). Still, these works may not indicate much about Taylor's private life. As he has warned many interviewers during his career, "I'm not trying to do autobiographical dances, that's not my thing." Among Taylor's honors are a Guggenheim Fellowship (1961), Emmy Award (Speaking in Tongues, 1991), Kennedy Center Award (1992), and National Medal of Arts (1993). |

| Robbins,

Jerome (1918-1998)

Jerome Robbins (1918-1998) was a bisexual choreographer and director.

He was both a great choreographer of classical ballet and a Broadway

innovator, but he was fearful that he might be outed. |

A portrait of Jerome Robbins in Three Virgins and a Devil (1941) by Carl Van Vechten. |

| Bisexual

choreographer and director Jerome Robbins was both a great choreographer

of classical ballet and a Broadway innovator, but he was fearful that he

might be outed, and his reputation was tarnished when--during the height

of McCarthyism--he "named names" during a meeting of the House

Un-American Activities Committee.

According to critic Clive Barnes, Jerome Robbins "was an extremely demanding man, not always popular with his dancers, although always respected. He was a perfectionist who sometimes, very quietly, reached perfection." From 1944 to 1997, Robbins choreographed 66 ballets and choreographed (and often also directed) fifteen Broadway musicals. During his extraordinarily prolific career he not only excelled in two different mediums, but he also worked with chameleon-like versatility, never seeming to repeat himself. Born Jerome Rabinowitz to Harry and Lena Rabinowitz on October 11, 1918 in New York City, he and his family soon moved to Weehawken, New Jersey. His father's corset business allowed young Robbins to attend New York University for one year, where he majored in chemistry, before a slump in business forced him to withdraw. Robbins had already started accompanying his sister to dance classes, which led to his professional debut in a Yiddish Art Theater production in 1937. For five summers Robbins choreographed and performed at the famous Pocono resort Lake Tamiment, in between dancing in four Broadway musicals, one choreographed by George Balanchine. Robbins was hired as a choreographer for the second season of Ballet Theatre (1940-1941). His meteoric career took off with his first ballet, Fancy Free (1944), to an original score by Leonard Bernstein. The ballet was an instant hit; and the composer and choreographer, both twenty-five years old, joined forces with lyricists Betty Comden and Adolph Green to create a musical out of Robbins' comic ballet of three sailors on leave in New York City: On the Town. The success of On the Town made Robbins the boy genius of two worlds: musical theater and concert dance. In the 1950s, Robbins began to direct as well as choreograph, creating such masterpieces as The King and I (1951), Bells Are Ringing (1956), Gypsy (1959), Fiddler on the Roof (1964), and, most notably, West Side Story (1957). Robbins' darkest hour occurred at the height of McCarthyism. In 1953 he named eight colleagues as members of the Communist Party during a House Un-American Activities Committee hearing. Robbins never explained or defended his motives for naming names. He may have testified to avoid being blacklisted on Broadway or out of fear of being outed as a homosexual. Many colleagues and others considered his behavior a betrayal and never forgave him for it. Unlike other directors of musicals, Robbins demanded that his actors dance as well as sing. His high expectations of the cast of West Side Story, for example, created the triple-threat performer. This landmark production in the history of musical theater was also the beginning of a new genre: musical tragedy. While librettist Arthur Laurents felt that the shared Jewishness of the collaborators was the greatest influence on the creation of West Side Story, surely the show was also influenced by the fact that seven members of the creative team were gay: Robbins, Laurents, composer Leonard Bernstein, lyricist Stephen Sondheim, set designer Oliver Smith, lighting designer Jean Rosenthal, and costume designer Irene Scharaff, in addition to the first actor to play Tony, Larry Kert. One result of the homosexuality of most of the creative team is that, despite the heterosexual plot line, West Side Story is nevertheless intensely homoerotic . The male characters are eroticized as much as the female characters, if not more so; and Riff seems to love Tony as much as Tony loves Maria. At the invitation of Balanchine, Robbins joined New York City Ballet as a dancer, choreographer, and Associate Director from 1949 through 1959. He returned to New York City Ballet as Ballet Master in 1969. For the next twenty years, the former king of Broadway choreographed numerous masterpieces of ballet, including Dances at a Gathering (1969), The Goldberg Variations (1971), Glass Pieces (1983), Ives, Songs (1988), and 2 & 3 Part Inventions (1994). There is little doubt that his ballets would have been more highly regarded, then and now, had they not been created in Balanchine's shadow. Robbins' classicism was not as dedicated to a strictly codified idiom as Balanchine's; rather, it was infused with theatricality and emotional expressiveness. Many of Robbins' ballets have a naturalness, a democratic air, because they translate (and transform) European (especially Russian) ballet conventions into a more familiar vernacular. Robbins' ballets are not about Americana, yet they are very American.

Shortly before the death of Balanchine in 1983, Robbins and Peter

Martins were named co-directors of New York City Ballet, a post Robbins

held until 1990. Robbins took a leave from New York City Ballet in 1988 to stage Jerome

Robbins' Broadway (1989), an anthology of dances and scenes

from eleven of his Broadway shows. It won the Tony Award for Best Musical

and ran 624 performances. Robbins the perfectionist was often his own worst enemy. He was

savagely demanding of his performers and unrelenting in his demands on

himself. High expectations ruled his personal life as well, as Robbins

pursued both men and women, but formed no permanent relationship. Robbins' ballet Facsimile (1946) reflects his bisexuality, as

two men and one woman vie for one another's affections. Ballet dancer Nora Kaye told reporters that she and Robbins were to be

wed in 1951; at the same time, Broadway dancer Buzz Miller and Robbins

were in the midst of their five-year live-in relationship (1950-1955).

Robbins' other romantic affairs included those with actor Montgomery Clift,

writer Christine Conrad, photographer Jesse Gerstein, and filmmaker Warren

Sonbert. On 29 July 1998, Robbins died of a stroke at the age of 79. His

numerous awards include one Emmy (Peter Pan), two Oscars (West

Side Story), four Tony Awards, the Kennedy Center Honors (1981), and a

National Medal of the Arts (1988). The greatest classical choreographer born in this country and a

Broadway innovator, Robbins took millions of people to a new place, as he

once said, a world "where things are not named." |

| Nureyev,

Rudolf (1938-1993)

Rudolf Nureyev (1938-1993) was the greatest dancer of his time.

He also gave the world a new and glamorous image of a sexually active gay

man. |

A portrait of Rudolph Nureyev by Richard Avedon. |

|

Enfant terrible, monstre sacré, and dieu de la danse are just some of the terms that describe the incomparable dancer, choreographer, and ballet director Rudolf Nureyev. Rudolf Hametovich Nureyev was born on a train somewhere in Siberia, about 1900 miles from Vladivostock, on March 17, 1938. The son of Muslim peasants, he was a small, malnourished, and highly sensitive child, bullied and tormented by other children. The young Rudolf's proficiency at folk-dancing brought him to the attention of two exiled ballerinas living in Ufa. They gave him classes and introduced him to the opera ballet company there. When Rudolf's father returned from service in World War II, he regularly beat his son for studying dance. The child dreamt "of a savior who would come, take me by the hand and rescue me from that mediocre life." However, he was rescued not by some prince, but by his own protean talent supported by unyielding will power. What seemed an impossible dream of studying ballet at the fabled Kirov school in Leningrad came true. At age 17, he enrolled in the Leningrad Ballet School, where he was an outstanding dancer but a rebellious student. He refused to join the Communist youth league, and he studied English privately. After graduation in 1958 he became a soloist with the Kirov Ballet. Three years later, while on tour with the Kirov Ballet in Paris, he learned that he was to be sent back to the USSR for flouting Soviet security regulations. As a consequence, he sought political asylum in France, making what came to be known as the great "leap to freedom." He was subsequently convicted of treason in absentia by a secret Soviet trial. He lived most of the rest of his life at risk of being kidnapped or assassinated. Nureyev's defection made headlines throughout the world. Overnight, he became a superstar. His physical beauty and sexual magnetism, coupled with his athletic ability, excited men and women alike. His seductive personality made him the darling of international society. Moreover, his bravura dancing, especially his stupendous jumps with multiple turns in the air, and his great risk-taking, changed the way male ballet dancers danced. His fame and charisma attracted new audiences to the ballet. Nureyev made his American debut in 1962, appearing to great acclaim on television and with Ruth Page's Chicago Opera Ballet. Later in 1962 he joined London's Royal Ballet as permanent guest artist. In so doing, he revitalized the company. Partnered with Margot Fonteyn, he gave new life to such classics as Giselle and Swan Lake and introduced such contemporary ballets such as Sir Frederick Ashton's Marguerite and Armand (1963). As artistic director, he formed his own touring companies and transformed the national ballet companies of Australia and Canada from provincial to world class. In 1983, he found the artistic base for which he longed when he became artistic director of the Paris Ballet. He remained in this position until 1989, when he resigned. However, he served as premier choreographer of the Paris Ballet until his death. Among his most successful works of choreography are his stagings of Romeo and Juliet, Manfred, and The Nutcracker. Nureyev also choreographed (and co-directed) a lavish film ballet of Don Quixote (1973). This work has recently been restored and presented as part of PBS's "Great Performances" series. An indefatigable performer, Nureyev for many years danced almost every day, sometimes with performances back-to-back. He appeared in cities throughout the world and attracted a large and diverse audience. As a result, he amassed a fortune, which he invested shrewdly, but also spent lavishly on houses and works of art. One of Nureyev's great contributions to ballet had to do with his sexual openness. Completely comfortable with his own sexuality, Nureyev expended no effort in presenting a heterosexual image on stage or off. Hence, he was able to concentrate on expressing music and choreography as it seemed appropriate to him. His openness helped liberate other male dancers from the obsession with maintaining a heterosexual image. Nureyev's sex life was as legendary--and frenetic--as his dancing. His sexual partners ranged from hustlers to the rich and famous. The large size of his penis was not only the subject of gossip, but it was also confirmed by photographs taken by Richard Avedon. Nureyev's most intense affair was with the Danish dancer Erik Bruhn (1928-1986). Bruhn possessed an elegant, refined, classical style, quite different from Nureyev's feral qualities. Yet in 1961 Nureyev felt that Bruhn was the only living dancer who had anything to teach him.

He sought out the older dancer and fell in love with him. Although the

dour Bruhn responded physically to Nureyev, the intense and turbulent

relationship that ensued was not a happy one, perhaps because Bruhn

suffered from professional jealousy and anxiety. As Nureyev's star rose,

Bruhn became reclusive and alcoholic. The dancers' physical relationship ended in the mid-1960s, but Nureyev

never ceased loving Bruhn. Nureyev also had a long-term relationship with director and archivist

Wallace Potts in the 1970s. In 1978, Nureyev was briefly infatuated with a

young dancer, Robert Tracy. Tracy moved into Nureyev's New York apartment,

where he stayed until evicted thirteen years later, treated, as he said,

"like a lackey." Nureyev and Tracy were both diagnosed with the AIDS virus in 1983. When

he learned that the dancer had left him nothing in his will, Tracy filed a

palimony suit against Nureyev's estate and received a settlement of about

$600,000. Nureyev died in Paris of AIDS-related complications on January 6, 1993.

He left the bulk of his fortune to establish foundations to promote dance

and medical research. The greatest dancer of his time, Nureyev thrilled millions of people

with his artistry. He also gave the world a new and glamorous image of a

sexually active gay man. |

| Nijinsky,

Vaslav (1889-1950)

Vaslav Nijinsky (1889-1950) was one of the greatest dancers and most

innovative choreographers in the history of ballet. |

Vaslav Nijinsky with his daughter in 1916. |

|

One of the greatest dancers in the history of ballet, Vaslav Fomich Nijinsky almost single-handedly reasserted the primacy of male dancers in ballet after a long period of decline. A radically innovative choreographer, the full extent of whose genius is only now being recognized, he embodied the sensuality and sexual ambiguity associated with the distinctive new art of the twentieth-century. Nijinsky was born on March 12, 1888 in the Russian city of Kiev, the son of Polish dancers who toured Russia as guest artists. He had already performed on stage with his parents when, at the age of ten, he was admitted to the St. Petersburg Imperial School of Ballet. There, as a ward of the Tsar, he also received an excellent academic education. Sexually precocious, he was reprimanded for masturbating, thus presaging his amazing autoerotic performance on stage in his ballet L'Après-midi d'un faune (1912). Nijinsky was a brilliant ballet student; and in 1907, after his graduation, he joined the Imperial ballet as a soloist, a rare achievement. He also fell in love with Prince Pavel Dimitrievitch Lvov, a wealthy nobleman in his early forties and himself an athlete. The prince provided Nijinsky with an apartment, a splendid wardrobe, and a magnificent diamond ring; and he also assisted Nijinsky's mother, who had been living in marginal poverty. When the Prince cooled toward him, Nijinsky had a brief liaison with another nobleman, Count Tishkievitch, but, he wrote, "I loved the prince, not the count." Nijinsky then met his match in the dynamic, thirty-five-year-old Sergei Diaghilev and joined the ballet company Diaghilev was preparing to take to Paris in 1909, the Ballets Russes. Nijinsky was the star attraction of their sensational success and was soon dubbed Le Dieu de la Danse. Nijinsky and Diaghilev became lovers, and Diaghilev used all his resources to create ballets designed to highlight Nijinsky's phenomenal artistry and sexual magnetism. For example, his roles as the Golden Slave in Scheherazade (1910) and as the androgynous scent of the rose in Le Spectre de la rose (1911) display the dancer's talent and charisma. Diaghilev also encouraged Nijinsky to choreograph ballets, giving him the finest dancers to work with and unprecedented amounts of rehearsal time. The four ballets that Nijinsky created, L'Après-midi d'un faune (1912), Le Sacre du printemps (1913), Jeux (1913), and Till Eulenspiegel (1916), were box-office failures but they are now considered, by virtue of their technical innovations, to be the foundation of modern dance. Nijinsky's ballets and the roles he danced are especially notable for their exploration of sexuality. Indeed, they were as scandalous for their sexual themes as for their radical balletic experimentations. Voyeurism, sexual primitivism, bisexuality, autoeroticism, and sexual ambiguity are all features of his work. Moreover, Nijinsky's own sexual charisma, and poetic acting, contributed powerfully to the erotic resonances of his performances. In 1913, while on a tour to South America, Nijinsky impulsively married a young Hungarian woman, Romola Pulsky, who had pursued him throughout Europe. The marriage ended his relationship with Diaghilev, who was outraged by the betrayal. At that time, there were no companies remotely comparable to Diaghilev's, so the split with his former lover left the dancer, soon encumbered by a child as well as a wife, with no way to pursue his career. The stress was intensified by the outbreak of World War I, which found him in Budapest. As a Russian citizen in Hungary, and therefore an enemy alien and prisoner of war, Nijinsky was unable to dance at all. Despite the war, Diaghilev arranged a tour of the Ballets Russes to the United States. He was also able to effect Nijinsky's release from Hungary to rejoin the company. Diaghilev met the dancer, his wife and baby daughter upon their arrival in New York City. The two men kissed and Nijinsky thrust his baby daughter into Diaghilev's arms, an action that infuriated his wife, who proceeded to make life unbearable for both men. As a result, Diaghilev returned to Europe, leaving the company to struggle across North America under Nijinsky's reluctant and inept management. Later in Spain, Diaghilev again invited Nijinsky to rejoin the company, but again Romola thwarted any reconciliation. The strain on Nijinsky was intense. His career in ruins, he recognized that his marriage had been a grave error. He was also depressed by the war and began to sympathize with revolutionaries in their loathing of materialism. Nijinsky may at this time have receded into delusion. Romola committed him to a mental institution, where drugs and experimental shock treatments (perhaps administered in an attempt to "cure" his homosexuality as well as his depression) effectively destroyed him. He lived, like a melancholy ghost, shuttled between private homes and institutions, until April 8, 1950, when he died of renal failure in London. |

| Molina,

Miguel de (1908-1993)

Miguel de Molina (1908-1993) reinvented the Spanish flamenco performance, but

his career was plagued by hostility toward his open gayness.

Miguel de Molina rose from poverty to become one of his country's most

celebrated flamenco singers. His wildly popular performances reinvented a

dance and music tradition that had grown stale for lack of innovation and

originality. Despite his success, however, Molina's open gayness and

gender-bending stage persona provoked hostile reactions that plagued his

career. The naturally effeminate Molina was forced from the stage on numerous

occasions and eventually found himself expelled from two countries. Yet,

despite this homophobic persecution, Molina never retreated into the

closet and refused to alter his feminine stage persona. Molina's life was as melodramatic as his music. Born Miguel Frías

in a small Spanish town near Málaga in 1908, he came from a

background of dire poverty. Expelled from school when a vengeful and sexually abusive priest

accused him of "unnatural acts" with other boys, little Miguel

ran away to Algeciras where he found employment cleaning a brothel.

Because he was only thirteen at the time, the prostitutes cared for him as

mothers and even arranged for a school teacher client to tutor him. Moving on at the age of seventeen, Molina found employment on the ship

of a Moroccan prince, serving in what was essentially the prince's male

harem. The prince soon fell out of political favor, however, and Molina

returned to Spain where he began organizing Tablas Flamencas, or

flamenco parties, for Granada's Gypsies. This experience constituted Molina's first full exposure to a musical

and dance tradition he already loved. By 1930, Molina arrived in Madrid

where he made increasingly good money organizing Tablas in the

capital. One year later, he decided the time had come for him to take to

the stage rather than to manage it. He appeared in a production of Manuel

de Falla's ballet El amor brujo, but soon developed his own act,

which combined flamenco and cabaret. Molina's notion was to reinvent flamenco performance by feminizing the

usual macho role taken by men. He sewed enormous two-meter-long sleeves,

which he called blouses, onto the traditional costume and even sang the

type of coplas, or popular songs, normally reserved for women. Although he danced with a female colleague, he nonetheless acquired the

name "La Miguela" and immediately met with enormous success. In

1933, he gave himself the name "de Molina." With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Molina fled to

Valencia and from there entertained Republican troops. Because he and his

dance partner Amalia Isaura became near mascots for the Levantine

Republicans, both found themselves vulnerable after the Fascist victory in

1939. Initially, a promoter closely connected to Franco's regime contracted

them to tour the country. This arrangement protected the dancers from

retribution, but in return they were paid a pitiful wage despite their

popularity. Tired of his status as war booty, Molina decided not to renew this

contract once it expired in 1942. Soon thereafter, government thugs

kidnapped him from the theater where he was then performing and tortured

him, pulling his hair out and beating him with their guns. Molina survived this abuse but then suffered sequestration in remote

Spanish towns. Unofficially banned from employment in Spain, Molina

finally fled to Argentina where he again met with great success. One year

later, however, the machinations of Franco's government forced his

expulsion from Argentina. Molina once again found himself in Spain without

work. In 1946, Molina fled to Mexico and soon thereafter settled in Buenos

Aires, allegedly under the personal protection of Argentina's most

powerful woman, Eva Perón. His customary success soon followed.

Although he claimed not to have been political, his identification with

Perónism caused many Argentinians to despise him. In 1960, he

withdrew from the entertainment world with some bitterness. By the time he died in 1993, Molina had regained some of the esteem in

which he had been held earlier, especially in Spain. He had, after all,

produced numerous theater reviews, starred in many films, and established

two significant signature songs that most Spaniards know by heart, "Ojos

Verdes" (Green Eyes) and "La bien Pagá" (The Woman

Well Paid). According to Molina's not always reliable autobiography, the

persecution he experienced at the hands of the Franco government had less

to do with hostility from Franco's officials (with whom he enjoyed great

popularity) than with the hatred and jealousy of a self-loathing, closeted

gay functionary serving under the powerful minister of foreign affairs.

Molina concluded that his nemesis begrudged him his openly gay, yet

professionally successful life. Serving Molina best through these tremendous setbacks was his unceasing

creativity. By reinventing the role of the male flamenco dancer,

feminizing his appearance and sound without rendering either

"mannered," Molina attracted audiences well beyond the genre's

traditionalists. Clothed in what seemed inverted dresses and singing songs

normally reserved for women, he attracted even the roughest of soldiers to

his flashy stage and movie persona. Unfortunately, Molina never returned to live in Spain even after its

transition to democracy. |

|

Robert Joffrey (1928-1988) created a major dance company and promoted gender

parity in ballet.

The great contributions of Robert Joffrey to American dance are his

creation of a major dance company and his distinguished work as teacher

and trainer of dancers. Dedicated to gender parity in ballet, he helped

elevate the status of the male dancer, making male virtuosity a priority

in his repertoire and in his classroom. Joffrey was born Anver Bey Abdullah Jaffa Khan Joffrey on December 24,

1928 in Seattle, the only child of a loveless marriage between a Pakhtun

Afghani father and an Italian mother. His parents owned a restaurant. As a small, sickly child, with bowed legs and turned in feet, Joffrey

had to wear casts on his feet and began studying ballet to strengthen his

frame. Fortunately, Seattle was blessed with exceptional ballet teachers.

He was introduced to the grand tradition of the Ballets Russes by Ivan

Novikoff. Later, he studied with Mary Ann Well, famous for producing

professional dancers of note. When he was sixteen, Joffrey met twenty-two-year-old Gerald Arpino,

then serving in the Coast Guard. "It was love at first sight,"

Aprino later recalled. They became lovers. Arpino moved into the Joffrey family home. Soon the

young men became artistic collaborators as well when Arpino began studying

ballet with Novikoff. Although their sexual intimacy ended soon after 1949, Joffrey and

Arpino shared a domestic relationship for forty-three years, one that

ended only upon Joffrey's death. Joffrey later studied at the High School of Performing Arts in New

York, and in 1949 and 1950 he danced with Roland Petit's Ballets de Paris.

But at 5 feet 4 inches tall, Joffrey realized that his height limited his

potential for a career as a dancer. He began to think of choreography and

teaching as ways to contribute to dance. Joffrey began to choreograph his own ballets. He scored an early

success with Persephone (1952). He also staged dances for musicals,

operas, and London's Ballet Rambert. In 1954 Joffrey formed his own small ensemble troupe, dedicated to

presenting work by himself and Arpino. This ensemble gradually grew into a

major national company that revolutionized American dance history. Based in New York City, the Joffrey Ballet distinguished itself in a

number of ways. It commissioned the work of modern choreographers (for

example, Twyla Tharp's Deuce Coupe in 1973), and it revived great

ballets of the international repertoire that were neglected by other

American companies (for example, work by Tudor, Massine, Nijinsky, and

Nijinska, as well as ten ballets by Frederick Ashton and evenings devoted

to Diaghilev masterpieces). Other milestones in the history of the company include Joffrey's

multi-media psychedelic ballet Astarte (music by Crome Syrcus,

1967) and Arpino's rock ballet Trinity (1970). Joffrey was an unusually gifted teacher. From the beginning, his

school, the American Ballet Center, trained many important dancers.

Joffrey dancers became known for their youthful sexual vitality and

brilliant physical technique. Joffrey's emphasis on male virtuousity was an attempt to redress the

gender imbalance that had developed in ballet, in part as a result of

Balanchine's famous dictum that "Ballet is woman." Joffrey's

commitment to improving the status of male dancers influenced both his

teaching and his and Arpino's choreography. The Joffrey Ballet Company became popular throughout the United States

and abroad. Sometimes criticized for its commercialism, the company made

ballet accessible to a large and diverse audience, including people who

were not already devotees of the form. The Joffrey's repertoire contained no overt homosexuality, but there

was a great deal of covert

homoeroticism

as a retinue of gorgeous, bare-chested, late adolescent dancers

unfailingly delighted the gay male audience. Although Arpino has repeatedly denied the presence of homoeroticism in

his work, his 1966 all-male ballet, Olympics, a tribute to

athletics, featured a suggestive pas de deux. During one curious phase, the men's costumes featured a distracting

athletic cup, shaped rather like half a large grapefruit. The cup

effectively covered the natural shape of the genitals--previously clearly

seen, especially under white or light colored tights--but gave the

impression of a giant tumor. Joffrey produced less choreography as he devoted himself to shaping his

company. Arpino became the house choreographer, while Joffrey synthesized

his own creative aesthetic with the Diaghilev legacy of nurturing the

talents of others. Joffrey was sexually promiscuous but discreet. His pattern was to have

Arpino at home for domestic stability, one principal romantic attachment,

and numerous one-night stands. In 1973, Joffrey fell in love with A. Aladar Marberger, a

twenty-six-year-old gay activist and manager of the Fischbach Gallery in

Manhattan. In the 1980s both men contracted AIDS. While Marberger was outspoken about his illness, Joffrey remained

silent. He was ashamed and wanted his obituary to say that he died of

liver disease and asthma. Arpino agreed to his pleas, but the secret could

not be maintained as AIDS took a staggering toll on the dance world in

general and on Joffrey's company in particular. Robert Joffrey died on March 25, 1988. Aladar Marberger died on

November 1, 1988. The Joffrey Ballet, now based in Chicago, survives under the direction

of Gerald Arpino. |

|

Isadora Duncan (1878-1927), the mother of modern dance, brought her feminist

consciousness to the stage. In her bohemian private life, she constantly

challenged society's rules.

Free thinking, free spirited, free moving Isadora Duncan brought her

bohemian feminist consciousness to the dance stage and changed the art of

dance forever. Although some critics ridiculed her flowing, expressive

movements and her leftist politics, Duncan brought flexibility and

self-expression to the hidebound world of classical dance. Duncan is known as the "mother of modern dance," but even

ballet was influenced by the radical élan of her ideas. In many

ways her life was tragic, but she left behind, not a sense of despair and

loss, but the dynamic imagination of a true original. Duncan was the child of the radically transformative era at the end of

the nineteenth century. Born to freethinking parents in San Francisco on

May 26, 1877, she was mostly raised by her mother, a lover of music,

literature, and the arts. Her mother earned money teaching piano lessons,

and it was not long before Isadora, who learned to dance following the

movements of the waves on the beaches near her home, was earning extra

cash too, teaching dance to younger children in the neighborhood. Duncan's influences were the movements she found in nature and the

passion of classical Greek drama. She hated the rigid structures of

ballet. She determined to create not only a new form of dance, but also a

new outlook on dance, where expressive movement would be an integral part

of every child's education, along with the usual academic subjects. When Duncan was a teenager, she and her mother traveled to Chicago and

New York, where she performed in theaters and vaudeville houses to less

than enthusiastic audiences. It was not until 1900 when she went to Europe

that she began to be taken seriously as a dancer. Although she began by

performing at private parties, soon she was touring the major stages of

Europe, galvanizing audiences with her "modern" dance. At the beginning of the twentieth century, ballet had become a

voyeuristic art, appealing largely to men who attended to watch women

performing in skimpy (for the day) tutus. Isadora Duncan introduced the

solo performance to dance audiences. Decrying restrictive women's

clothing, she shed her corset and petticoats and danced barefoot in

simple, flowing, Grecian-style tunics adorned with long, colorful scarves.

Her dances concerned such subjects as motherhood, love, and grief, and her

audiences were filled with women. Almost as titillating as her radical approach to dance was Duncan's

bohemian personal life. She was an outspoken socialist and advocate of

women's rights who constantly challenged society's rules. Claiming she did

not believe in marriage or monogamy, she had two children with two of her

many male lovers. (Both children were drowned in an accident in 1913.) She also attended Natalie Barney's Paris salons and had female lovers,

among them writer Mercedes de Acosta, about whom she wrote, "My

kisses like a swarm of bees / Would find their way between thy knees / And

suck the honey from thy lips / Embracing thy too slender hips." Duncan achieved her dream of creating a new, well-rounded form of

education. She established schools of the Duncan method in Berlin, Paris,

London, and Moscow. But her life was tragically cut short, when, at the

age of 49, one of her flamboyant long scarves caught in the wheel of the

sports car she was driving and strangled her. |

| Bruhn,

Erik (1928-1986)

Erik Bruhn (1928-1986) was the premier male dancer of the 1950s and

epitomized the handsome prince and cavalier on the international ballet

stage of the decade. |

Erik Bruhn (second

from left) visiting backstage at the New York City Ballet. The group

included (left to right) Diana Adams, Bruhn, Violette Verdy, Sonia Arova,

and Rudolph Nureyev. |

|

Erik Bruhn was the premier male dancer of the 1950s and epitomized the ethereally handsome prince and cavalier on the international ballet stage of the decade. Combining flawless technique with an understanding of modern conflicted psychology, he set the standard by which the next generation of dancers, including Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Peter Schaufuss, and Peter Martins, measured their success. Born on October 3, 1928 in Copenhagen, Bruhn was the fourth child of Ellen Evers Bruhn, the owner of a successful hair salon. After the departure of his father when Erik was five years old, he was the sole male in a household with six women, five of them his seniors. An introspective child who was his mother's favorite, Erik was enrolled in dance classes at the age of six in part to counter signs of social withdrawal. He took to dance like a duck to water; three years later he auditioned for the Royal Danish Ballet School where he studied from 1937 to 1947. With his classic Nordic good looks, agility, and musicality, Bruhn seemed made for the August Bournonville technique taught at the school. He worked obsessively to master the technique's purity of line, lightness of jump, and clean footwork. Although Bruhn performed the works of the Royal Danish Ballet to perfection without any apparent effort, he yearned to reach beyond mere technique. In 1947, he accepted an invitation to perform with London's Metropolitan Ballet. This experience would be the first step in his lifelong quest for growth as a dancer. For the next decade, his career would be divided between starring with the Royal Danish Ballet and dancing as a guest artist with such leading companies as American Ballet Theater, the Australian Ballet, and the Stuttgart Ballet. On May 1, 1955, Bruhn partnered British ballerina Alicia Markova at the old Metropolitan Opera House in New York in his stunning debut as Albrecht in the Ballet Theater production of Giselle (1884, choreographed by Marius Petipa after Coralli and Perrot, with a score by Adolphe-Charles Adam). A landmark ballet experience for audience members such as William Como of Dance Magazine and dance critic John Martin of The New York Times, this one performance elevated Bruhn to superstardom. From then on, he was the reigning prince in the world of ballet and was instrumental in changing the role of men in classical dance. Bruhn's self-critical and brooding personality, however, kept him from enjoying his triumphs. Everyone may have loved him, but he loved no one--including himself. His reserve and tendency to over-analyze had been his burden and limitation as a child and shadowed his adulthood and maturity as well. In May 1961, Bruhn was celebrated in a major article in Time and acclaimed for recent performances as different as Jean the Valet in Birgit Cullberg's Miss Julie (1950, with a score by Ture Rangström) and Don José in Roland Petit's Carmen (1949, with a score by Georges Bizet). He also virtually owned the roles of Albrecht in Giselle, James in La Sylphide (1836, choreographed by August Bournonville, with a score by Herman Severin von Løvenskjold), and Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake (1895, choreographed by Lev Ivanov and Marius Petipa, with a score by Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky). At age 32, Bruhn was at the peak of his career, yet he felt stalled personally and artistically. He was desperate for renewal of some kind. This renewal came in the form of Rudolf Nureyev, a twenty-three-year-old Russian, who on June 17, 1961 announced his presence on the international dance scene by defecting from the Soviet Union in a headline-grabbing leap to freedom in Paris. Nureyev, all ambition and animal charisma, had said that of all the dancers in the world only Bruhn had something to teach him. In a few short weeks, Nureyev found his way to Copenhagen to learn whatever Bruhn could teach him; ironically, Maria Tallchief, with whom Bruhn had had a brief affair and dancing partnership, engineered the introduction that would bring her own claim on Bruhn to an abrupt end. As fate would have it, Bruhn and Nureyev, as different as Apollo and Dionysus, were fiercely attracted to one another. Although neither had any previous serious romantic attachments to men (Bruhn had been engaged to Bulgarian ballerina Sonia Arova for about five years before his affair with Tallchief), they formed an intense, turbulent, and profoundly transformative relationship that Bruhn later referred to as "pure Strindberg." Until their dying days, each regarded the other as the love of his life despite the collapse of the sexual dimensions of their relationship by the mid-1960s.

In 1963, Bruhn began to experience severe stomach pain that repeated

medical examinations failed to explain. Attributing the problem to

psychosomatic causes, he decided to retire in late 1971 to reduce the

stress in his life. Even after retirement, however, the pains continued

and grew so critical that in 1973 he underwent emergency surgery that

revealed a perforated ulcer. In 1974, restored to health at age 46, Bruhn returned to dancing, but

not as a regal Prince. In a production of Giselle featuring

ex-lover Nureyev in his former signature role of Albrecht, Bruhn scored an

astounding success as Madge, the evil witch. This triumph signaled the start of the second phase of Bruhn's dancing

career. His versatility and acting skill enabled him to make a graceful

transition from dancing Prince Ideal to performing vividly realized

character parts such as Dr. Coppelius in Coppelia (1975,

choreographed by Bruhn after the 1884 Petipa original, with a score by Leo

Delibes), The Moor in The Moor's Pavane (1949, choreographed by José

Limon, with a score by Henry Purcell), and the title role in Rasputin--The

Holy Devil (1978, choreographed by James Clouser, with a score by St.

Elmo's Fire Band). The dancer's later triumphs brought renewed recognition of his

uniqueness in ballet: his ability to combine flawless technique, intense

character study, and total commitment to create stage performances that

remained indelible to audiences. Bruhn was appointed Artistic Director of the National Ballet of Canada

in 1983, a position that he fulfilled admirably. By this time he had

cemented a stable and fulfilling relationship with dancer and

choreographer Constantin Patsalas, while Nureyev, his great but impossible

love, remained a close friend. Bruhn died of lung cancer in Toronto on April 1, 1986. |

| Allan,

Maud (1873-1956)

Maud Allan (1873-1956) achieved fame as a "Salome Dancer," but she

is best remembered for a libel suit she brought against a newspaper publisher

for alleging that she was a lesbian.

In the early years of the twentieth century Maud Allan achieved

worldwide renown as the "Salome Dancer" for her stunning

performances of the best-known piece in her repertoire, The Vision of

Salome. She is also remembered for a lawsuit that she brought against

a newspaper publisher for alleging that she was a lesbian. Although it was

Allan who charged libel, in court her opponent tried to put both her and

Oscar Wilde's play Salome on trial. Early Life and Education Born Beulah Maud Durrant in 1873 in Toronto, Allan was the daughter of

William Allan Durrant, a shoemaker, and Isa (also known as Isabella)

Matilda Hutchinson Durrant. Three years later William Durrant moved to San

Francisco, where he bounced from job to job, mainly in the shoe

manufacturing industry. In 1879 Isabella Durrant followed with their two

children, Maud and her brother William Henry Theodore (usually known as

Theo). As a youngster Allan excelled at arts and crafts--carving, clay

modeling, sketching and sewing. She also showed talent for music and

studied to be a concert pianist. It may be that the dream of a career for

Allan on the concert stage was at least as much her mother's as her own,

but the young woman showed sufficient promise that her teacher, Eugene

Bonelli of the San Francisco Grand Academy of Music, advised her to go to

Germany to complete her musical studies. In February 1895 Allan set off for Berlin, where she was admitted to

the Hochschule für Musik. Hardly had she begun her studies, however,

when she received the shocking news that her brother had been arrested for

murder. In April the bodies of two young women were discovered in San

Francisco's Emmanuel Baptist Church, where Theo Durrant was the assistant

Sunday School superintendent. The grisly murders, which were compared to

the crimes of Jack the Ripper, received sensational and sometimes

speculative coverage in the California press. Over 3,600 potential jurors

needed to be examined before twelve could be chosen to hear the case. On November 1, the jury found Durrant guilty of first-degree murder. He

was sentenced to be put to death on February 21, 1896, but appeals of the

case caused the execution to be put off three times. Durrant was finally

hanged for murder on January 7, 1898. Throughout this entire period Maud Allan, at her brother's request,

remained in Europe. The siblings, who had always been extremely close,

kept in frequent contact by letter. Allan held out hope for a reprieve

until the very end, and she never stopped asserting her belief in her

brother's innocence. With little money coming from her family in America, Allan needed to

work while pursuing her studies. She sometimes gave English lessons but

earned little in this way. She had greater success when she joined with

several other people in a corset-making business. (Allan designed, sewed

and even modeled the product.) On one occasion she put her drawing skills

to use, illustrating a sex manual for women, Illustriertes

Konversations-Lexikon der Frau (1900). Dancing Career Although Allan continued her piano studies as her mother wished, she

had become intrigued with the idea of "dancing as an art of poetical

and musical expression." A pivotal point in her career came when she

met Belgian musician and critic Marcel Rémy, who encouraged her to

explore and develop her thoughts on dance and who wrote the music for The

Vision of Salome, the performance piece for which Allan would be

famous. Allan would always emphasize that she had never taken a dancing lesson

and insist that her style of dancing was entirely her own creation. What

rankled her especially was to be compared to Isadora Duncan, whom she

strongly disliked. While Allan's claims were overstated, she did show

great imagination and creativity. These, combined with her unconventional

costumes (which she designed and sometimes sewed herself), lent

originality to her art. Her musicality and natural grace allowed her to

suit her movements to music most effectively. As one reviewer put it,

"she simply alchemized a piece of music for you." Although Allan's repertoire consisted of a wide variety of pieces

including Mendelssohn's Spring Song, Schubert's Ave Maria,

and Chopin's Marche funèbre, it was Rémy's The

Vision of Salome that made her reputation and earned her the nickname

"the Salome Dancer." Her interpretation of the piece was all the

more powerful because Rémy had caused her to associate the

execution of John the Baptist with that of her own brother, thus evoking

an especially passionate performance of this work.

In 1908 Allan went to London and took the city by storm, giving more

than 250 performances that year. As a result of her fame, she received the

patronage of members of royalty, as well as Prime Minister Herbert Asquith

and his wife Margot. Allan developed a close friendship with Margot

Asquith, who for many years paid the rent for Allan's luxurious living

quarters in the west wing of Holford House, a villa overlooking Regent's

Park. In 1910 Allan left Europe and toured extensively for several years,

performing in America, Africa, Asia, and Australia. In 1915 she went to

California to spend time with her parents. During that sojourn she played

the title role in a silent film called The Rugmaker's Daughter. It

featured excerpts of three of her dances, including The Vision of

Salome. No copies of this film are known to survive. "The Cult of the Clitoris" Libel Case In 1916 Allan returned to England in hopes of reviving her faltering

career. In 1918 she became involved in a bizarre court case in connection

with her performance in a production of Oscar Wilde's Salome. The

case was a tangled thicket of personal and political animosity, as well as

homophobia

, anti-Semitism, and war-time hysteria. Allan sued for libel against an Independent Member of Parliament, Noel

Pemberton Billing. In addition to his political career he ran a newspaper

called the Imperialist, later renamed the Vigilante, which

he used to promulgate his views that Germany was a thoroughly degenerate

country owing to the power of Jews and homosexuals there and that German

agents were attempting to weaken the moral fabric of Britain by luring its

citizens into vice. In the January 26, 1918 issue of the Imperialist, Billing

claimed that the Germans had a "Black Book" containing the names

of 47,000 British men and women who were vulnerable to blackmail or had

betrayed state secrets because of their "sexual peculiarities."

His source for this claim was Captain Harold Spencer, who had been

invalided out of the British Army and British Secret Service for

"delusional insanity." Billing invited a lawsuit from Allan by printing an item in the

February 16, 1918 issue of the Vigilante headlined "The Cult

of the Clitoris." In the brief article he suggested that subscribers

to Allan's upcoming private performance of Wilde's Salome were

likely to be among the 47,000 listed in the "Black Book." The use of the word clitoris was a calculated one by Billing and

Spencer. The latter testified that, in the course of searching for a

headline "that would only be understood by those whom it should be

understood by," he had elicited the word from a village doctor, who

had informed him that the clitoris was an "organ that, when unduly

excited . . . possessed the most dreadful influence on any woman...."

Allan's acknowledgment of knowing the word was presented as evidence of

sexual perversion. Billing further used innuendo by introducing the fact that Allan was

the sister of a convicted murderer. His argument was that murder showed

evidence of sadism (defined, in the testimony of Spencer, as "the

lust for dead bodies"), which Billing alleged was hereditary. He

discussed various perversions that he claimed to find in Wilde's Salome,

implying that a performer willing to depict these might well have them

herself. He also tried to insinuate that Allan had an unusually close

friendship with Margot Asquith. Another witness, Eileen Villiers-Stuart, who claimed to have seen the

"Black Book," testified that the names of both Herbert and

Margot Asquith were in it (along with that of Charles Darling, the judge

presiding in the case). On the final day of the trial, Billing suddenly claimed that he had

never suggested that Allan was a lesbian, only that "she was

pandering to those who practised unnatural vice by [her]

performance." Following long and rather confusing instructions from the judge, the

jury deliberated for less than an hour and a half before returning a

verdict in Billing's favor. Later Years After the trial Allan resumed her career, but her popularity soon

waned. For at least ten years, from the late 1920s to 1938, Allan shared the

west wing of Holford House with Verna Aldrich, her secretary who became

her lover. Allan lived out her final years in California. A film loosely based on

her life, Salome, Where She Danced, was directed by Charles Lamont

and produced by Walter Wanger in 1951. Allan died October 7, 1956 at the age of eighty-four. |

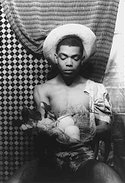

| Ailey,

Alvin (1931-1989)

Alvin Ailey (1931-1989), an African-American dancer and choreographer,

celebrated his heritage and translated his pain into art. |

Alvin Ailey in 1955 |

| As

a dancer, Alvin Ailey was noted for his sexual charisma. Lena Horne

famously described him as "like a young lion and yet like an earth

man." But he achieved international acclaim as a choreographer. His

company has performed before an estimated 15,000,000 people in 48 states

and 45 countries.

Ailey was born on January 5, 1931 in direst poverty in the Brazos Valley of Texas. His father abandoned him and his mother three months later. At various stages of his life Ailey had to contend with racism, homophobia , issues of political correctness, exploitative sexual partners, and venal management. In the face of all these obstacles, he triumphed as a creative genius. But homophobia, especially that of his mother, undermined his sense of worth as a man and helped make his personal life a tragedy. When Ailey was a child, he moved with his mother to Los Angeles, where she secured work in an aircraft factory. School was a haven for him. He spent long hours in the library, reading and writing poetry. The large, solidly built boy who looked like fullback material managed to avoid contact sports--and avoid being stigmatized as a sissy--by taking up gymnastics. At the age of 18, Ailey caught the eye of Lester Horton, a white dancer, teacher, and choreographer who had created in Los Angeles the first multi-racial dance company in the United States. With Horton, Ailey found an emotional home and quickly learned dance styles and techniques from classical ballet to Native American dance. He performed in Horton's company and found work in Hollywood films and eventually succeeded Horton as director upon the latter's death in 1953. For the first two years that Ailey danced with the Lester Horton company, he kept his life in dance a secret from his mother. When she first came to his dressing room and saw him in stage makeup, she slapped his face. Ailey moved to New York in 1954 to dance on Broadway. He appeared in House of Flowers (1954), with Harry Belafonte in Sing Man Sing (1956), and with Lena Horne in Jamaica (1957). He also studied with teachers such as Martha Graham, Hanya Holm, and Karel Shook, while beginning to choreograph pieces of his own. In 1957, Ailey formed his own group, which presented its inaugural concert on March 30, 1958. Among the dances premiered in the inaugural concert was his Blues Suite, a work deriving from blues songs that expresses the pain and anger of African Americans. With its combination of ballet, modern dance, jazz and black dance techniques, plus flamboyant theatricality and intense emotional appeal, Blues Suite was an instant success and defined Ailey's particular genius. In 1960, for his company's third season Ailey created his masterpiece, Revelations. Based on African-American spirituals and gospel music, it is perhaps the most popular ballet created in the twentieth century. While Ailey continued to choreograph for his own company, he created dances for other companies as well. For example, in 1973 he created Ariadne for the Harkness Ballet, with Maria Tallchief in the title role; and in 1983 he devised Precipice for the Paris Opera. Ailey was proud that his company was multi-racial. On the one hand, he wanted to give black dancers, who had often been discriminated against by other dance companies, an opportunity to dance; but he also wanted to transcend the "negritude" issue. His company employed dancers, composers, and choreographers of all hues based entirely on their artistic talent. While Ailey was pleased that the State Department sponsored his company's first overseas tour in 1962, he suspected that the sponsors' motives were propagandistic rather than altruistic as they wanted to demonstrate that "a modern Negro dance group" could flourish in the United States. Ailey was profoundly honored when the American Ballet Theater commissioned The River (1970), to music of Duke Ellington. He looked upon the commission as an opportunity to work with some of the best ballet dancers in the world, particularly with the great dramatic ballerina Sally Wilson. However, he was deeply disappointed when ABT insisted that the leading male role be danced by the only black man in the company, who was a conspicuously mediocre dancer. Although his company was sometimes described as patriarchal, with male dancers the center of attention, Ailey was also known for fostering the careers of several important female dancers, most notably Judith Jameson, who debuted with the company in 1965 and who spoke of Ailey as a great teacher. One of Ailey's great successes was Cry (1971), which he dedicated to his mother and black women everywhere and which became a signature piece for Jameson.

Ailey was a loving man, who was adored by many devoted friends and who

functioned as a father figure to his dancers. However, his personal and

professional lives were dogged with problems. Abused by lovers, he seemed

in later life to enjoy the company of street hustlers. Similarly, he

entrusted management and money matters to people who victimized him. The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre did not secure a permanent home

and stable management until 1979, when the company and school moved into

splendid facilities in the Broadway theater district of Manhattan. But by

this time, Ailey had become erratic. He was addicted to cocaine,

increasingly crippled by arthritis, and dependent on lithium. Like many men of his generation, including Jerome Robbins, for example,

Ailey was deeply ashamed of his homosexuality. For years, he refused to

consider an autobiography because "my mother wouldn't like it."

When he finally did collaborate on an autobiography, it was sexually

sanitized, notwithstanding the fact that it was to be published

posthumously. To spare his mother the social stigma of his death of AIDS

in 1989, Ailey asked his doctor to announce that he had died of terminal

blood dyscrasia. Although the choreographer could sincerely dance "I've been 'buked

and I've been scorned," he nevertheless managed to celebrate the

beauty of his heritage and translate his pain into art. His ballets embody

his aspirations for all-encompassing love and compassion. They still rock

the soul of a worldwide audience. |

| Dance